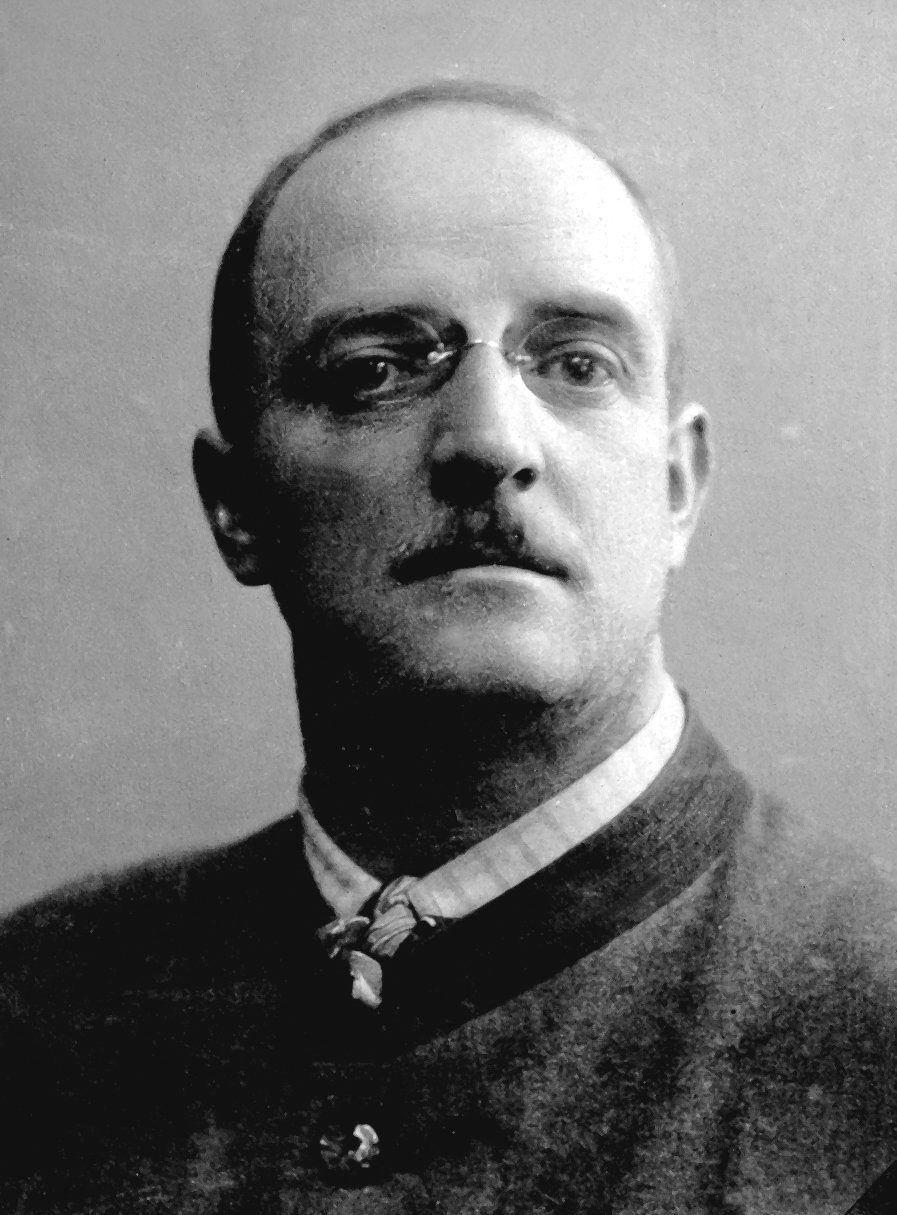

Josef WITTERNIGG was born in Bleiburg (Pliberk), Carinthia (in southeastern Austria) on October 12, 1881. He was a skilled hat maker & social democratic politician, and he was registered as having no religion.

His wife was the social democratic politician Anna WITTERNIGG, née Schwabeneder, and they had two children, Margarethe and Josef.

The family had local citizenship rights in Salzburg and had lived in the upper middle class palatial »Farber Houses« on the Rainerstraße since 1918.

Until the outlawing of the Social Democratic Labor Party (SDAP) in February 1934, Anna WITTERNIGG represented it in the Salzburg State legislature, chaired the party’s state women’s committee, and was a member of the nationwide Women’s Central Committee of the SDAP.

Her husband Josef was a member of the Salzburg city council, chairman of its social democratic caucus, state legislature representative and member of the Austrian National Council.

When the party leadership in Vienna called for a general strike on February 12, 1934 Josef WITTERNIGG was one of the key figures as the Salzburg SDAP gave up without a fight. The telephone number 459 of the party state headquarters in the Workers’ Home at 21 Paris-Lodron-Straße had been tapped by the police on »preventive grounds« and police agents were conspicuously posted around the Workers’ Home.

The police watching the building noted who entered and left it on the morning of February 12, 1934, including party official and vice-governor of Salzburg Robert Preussler, state councillor Karl EMMINGER, city council members Georg LEITNER, Heinz Kraupner and Franz Peyerl. National Councilman Josef WITTERNIGG was also seen there and as leader of the general strike he was overheard repeating the code phrase »Fritz has arrived« on the tapped telephone as he let his comrades know that the strike was underway.

One of the comrades didn’t understand the code phrase and it had to be explained to him – and that was logged meticulously by the police. On the same day the social democratic party officials were all arrested, including EMMINGER and WITTERNIGG who had immunity because of their legislative positions – »who forfeited their immunity due to being apprehended in the act.«

Many of their associates who came to the Workers’ Home for information were also arrested »in order to deprive them of the possibility to follow any instructions regarding the general strike.«

Both the authorities and the would-be strike leaders knew that on April 21, 1933 the authoritarian government of Engelbert Dollfuss had banned all strikes against any enterprises that affected the federal government or the public welfare.

Just calling for a strike was punishable by a fine of up to 2,000 schillings or imprisonment of up to six months. Strikers were threatened with being fired. The Social Democratic Party leadership had failed to call for a general strike in the spring of 1933 when they might have had more success.

The Social Democratic officials were also members of the outlawed party militia (the Republican Guard) and they were treated as coup plotters and traitors rather than as strike leaders.

The February 20, 1934 charges of the Federal Police in Salzburg »against Emminger Karl, Preussler Robert, WITTERNIGG Josef et Consorten [associates] for the crime of treason according to § 58 St.G. [Austrian criminal code]« began with the stereotypical justification:

The Social Democratic Party has made many attempts in recent years to arm the members of the dissolved Republican Guard with prohibited weapons and to promote a coup against the Federal government in order to take power and establish a dictatorship of the proletariat.

The 8 page long charge of the Federal Police in Salzburg, is included in the »Februarrevolte 1934« file of the Salzburg State Court

The leaders of the Republican Guard that had been illegal since the Spring of 1933 were all »known to the police«: state commander Karl EMMINGER, alternate state commander Georg LEITNER, district commander Johann WAGNER, group leader Anton SCHUBERT and others.

The Republican Guard militia of the SDAP was committed by its statutes to defend the democratic Austrian Republic and its constitution. It was supposed to mobilize against anti-democratic attempts to seize power but it had made no attempt to fight against its dissolution by the authoritarian Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss.

It did continue an underground existence but an armed uprising was considered hopeless because it lacked sufficient arms and battle-hardened troops. Nonetheless there was some armed resistance against Austro-fascism – in places that are well known, as are their victims.

In Salzburg the Social-democratic State leadership was ready to lead a general strike and mobilize the Republican Guard – which could have at least functioned as an unarmed strike defense operation had the strike call had been issued and strictly adhered to – but that was an illusion.

Instead without resistance the police were able to search workers’ homes, apartments, coal cellars and attics looking for evidence of the supposed coup attempt.

In the attic of the Workers’ Home on the Paris-Lodron-Straße they did find two Mannlicher military rifles, two sawed off shotguns altered for firing case shot, four Flobert guns [guns designed for indoor target shooting and useless for combat], four rifle barrels, 2,150 rifle bullets, 71 rifle and pistol bullets (dum-dums), 550 case shot munitions, three bayonets, six steel rods, seven bullwhips, 21 pick axes, eight wooden dummy hand grenades, eight water canteens and 50 field dressing bandages [in other words, exactly 4 guns useable for fighting].

The police and the government knew in any case that the Republican Guard was in no condition to mount a coup with these weapons – which were stored in known arsenals and which would be easy to confiscate.

An armed uprising would have required political and military preparation that didn’t exist.

The police found nothing of the sort, but in their search of the Workers’ Home they did find a Republican Guard minute book from the time when it had still been legal and which included an »alarm plan« (with mustering points and 47 activists) that could be implemented if there was an attempt to overthrow the republic.

The authoritarian Dollfuss regime took that as a scenario for violence that they publicized to justify their own violence.

The government – Austria had been a dictatorship based on a wartime law since March 1933 – attempted to make a credible case that the Social Democratic Labor Party and its Republican Guard were a threat to the city of Salzburg, like Vienna, Linz and other places.

As the government oriented Reichspost put it on March 2, 1934:

Social Democratic Deployment Plan Found.

According to this deployment plan [of the Republican Guard] the city of Salzburg would be divided into nine sections and each section would have its own combat force.

The Mönchsberg and the Kapuzinerberg would be occupied immediately and that would place the bridges and Salzach crossings under machinegun fire.

Then the police headquarters, the police barracks and the army would be taken by surprise attacks.

This misconstruction of the »deployment plan« by a government mouthpiece described a coup attempt that was never even planned, never mind attempted – so there couldn’t have been a foiled coup attempt.

It is worth noting that there was one act of violence on the night of February 13, 1934 in the Gnigl rail yards, but it went unmentioned because it didn’t fit the picture of a coup attempt against the government.

A rail yard steam engine had fallen into the turntable pit, blocking the roundhouse and preventing locomotives from leaving. But an investigation into this act of sabotage found nothing indicating a coup attempt: a fireman named Hans Frosch who had been seen locating his name on a work roster was suspected.

The process against Frosch, a member of the SDAP and the Republican Guard, had to be dropped because of a lack of evidence, though the »suspicion [was] not dismissed«. So when Hans Frosch was released on April 17, 1934 he remained under suspicion and that meant he had no claim to compensation for his arrest and he lost his job: fired from the railroad, his income eliminated, fate unknown – the usual fate of »little people« standing in the shadows of prominent historical figures.

The criminal file 1666/34 of the Vienna State Court »against Otto Bauer and comrades«, is often cited so it is well known that the criminal process against the party leadership for »conspiracy to commit treason« failed to come to trial despite the armed resistance in »Red Vienna«.

As a result those accused were unable to make an issue in court of the illegitimacy of the Dolfuss government that had gained power through a coup or breach of the constitution.

Then the Vienna court rejected the claims for compensation by the uncharged and freed Social Democrats, leaving them under suspicion of being coup masterminds and traitors.

It was no different in Salzburg. Despite the Salzburg court’s four volume set of files marked »do not destroy« & titled »Februarrevolte [February revolt] 1934« (13 Vr 352/34) the process against the Social Democrats in 1934 seems to have fallen into pit of forgetfulness.

Many of them fail to appear in the volume on Resistance and Persecution in Salzburg 1934-1945 that was published in 1991.1

But it is worth while to read the »Februarrevolte 1934« files – to see the police interrogation reports, the records of seized materials, and the hand written statements of the accused. These make it clear why those arrested on February 12, 1934 for being suspected »of the crime of treason« were released on their own recognizance on May 25th – and were »released from persecution« (i.e. from any possible further legal proceedings) on February 25, 1935.

The freed and »released from persecution« Social Democratic politicians who were neither charged nor convicted should have no longer been under any suspicion of treason. But when they sought compensation for their arrest they discovered that they still were.

On March 28, 1935 the Salzburg court ruled that they had no claim for compensation »for damages suffered from their arrest« because the »suspicion [is] not eliminated«. Josef WITTERNIGG rejected the conclusion, saying

I’m not a coup plotter, I’m a republican! I’m not a fascist, but a Social Democrat […]

The chief goal of the Social Democracy was to defend the democratic republic against fascism of any kind.

The appeal of the complainants against the court’s decision was denied by the court of appeals in Innsbruck on June 5, 1935. The court also denied them permission to leave for Czechoslovakia.

Josef WITTERNIGG wanted to go into exile legally – to join Otto Bauer and the other leaders of the outlawed Social Democratic party who had been in exile since February 1934.

Otto Bauer (the unifying figure of the SDAP in the First Republic, representative of balanced politics, theoretician, and procrastinator) had wanted to avoid the February fight.

The party leadership’s capitulation course and failure to resist in February 1934 had alienated and embittered the younger generation – an outrage felt by the party leaders in Salzburg who were being denounced as »coup plotters« and who were still being kept under police observation as suspected traitors.

But in any case we know that nearly 2,000 people, mostly members of the banned SDAP, attended the funeral of Josef WITTERNIGG when he died on February 28, 1937 – a sign of loyalty and respect.

His widow Anne, who survived both dictatorships, received a victims’ compensation pension after Austria was liberated because her husband had died at age 56 from injuries received while being politically persecuted under the Austrian dictatorship.

Anna WITTERNIGG was active in the revived Austrian Socialist Party after Salzburg’s liberation and the 77 year old widow died on May 29, 1967.

Her daughter Margarethe, an art historian in Vienna, had already died in 1951 and her son Josef, an Architect, lived in Salzburg until he died in 2000.

1 Social Democrat who were judicially persecuted in 1934 but who were not mentioned in the Dokumentation Widerstand und Verfolgung in Salzburg 1934-1945 included: Simon Abram (Suicide in Salzburg on February 29, 1940). Anton Baronit (fate unknown), Karl Braunbock (died on March 20, 1945), Hans Frosch (fate unknown), Maria Grabner (persecuted by the Nazi regime but survived), Konrad Pausch (died on April 25, 1945), Felix Schwab (survivor), Karl Wagner (exile, survivor), Georg LEITNER (vice-commander of the Salzburg state Republican guard persecuted, by the Nazi-Regime, and died on October 27, 1947 from his injuries as a prisoner) and Johann REITER (Group leader of the Republican Guard in Lehen, who was shot to death in Vienna-Kagran on July 25, 1940 for refusing military service).

Those who were mentioned in the 1991 book included Social Democratic functionaries Robert Preussler, Karl EMMINGER, Johann WAGNER and WITTERNIGG (who was persecuted in 1934 and didn’t live to see Salzburg’s liberation on May 4, 1945.

In 1962 streets in Salzburg-south were named after Robert Preussler, Karl EMMINGER and Josef WITTERNIGG.

Source

- Salzburg city and state archives

Translation: Stan Nadel

Stumbling Stone

Laid 02.07.2014 at Salzburg, Rainerstraße 2