The files of the Salzburg »Special Court« that issued 71 death sentences in the five and a half years of WWII (most of which were carried out in the Munich–Stadelheim prison) were generally shredded at the end of the war.

But the Munich prison’s implementation files were preserved in the Bavarian Main State Archives and they often include mimeographed copies of Salzburg death sentences of Nazi victims who would otherwise be unknown. The personal details of three Italian citizens sentenced to death by the Salzburg Special Court on August 2, 1944 are also known only from these implementation files:

• Pietro PIRONI was born in Cesena, Emilia-Romagna, on February 22, 1922. He was the son of Malvina and Primo Pironi from Gattolino – an unmarried philosophy student who had completed his military service;

• Giuliano SBIGOLI was born in Florence on October 22, 1923. He was the son of Agostina and Gino Sbigoli from Florence – an unmarried mechanic who had completed his military service;

• Remo SOTTILI was born in Regello (near Florence) on August 23, 1911. He was the son of Ida and Guido Sottili from Donnini di Regello – a vice-brigadier of the Bologna police married to Clementina Curioli from Ferrara, and who had also completed his military service.

Without the implementation files with their included court judgements we wouldn’t know anything about the other two Italians tried by the Salzburg court on August 2, 1944 who were declared innocent. Those two were:

• Goffredo BONCIANI who was born in Florence on February 7, 1922 – an unmarried law student who had completed his military service;

• Vasco POGGESI who was born in San Giovanni (near Arezzo in Tuscany) on August 29, 1922 – an unmarried electrician who had completed his military service.

That the two Italians who were declared innocent were nonetheless victims of the Nazis can be reconstructed from the criminal files KLs 76/44 of August 2, 1944. These judicial records only noted the »criminal acts« of the Italians and ignored those of the Nazi authorities.

The court noted the military service of the Italians but failed to note their abduction by the German occupation authorities in Italy. Designated as »civilian workers« (forced laborers) or as »military internees« (Prisoners of War) these Italians could be prosecuted by the Gestapo and the courts for the »crime« of breaking their employment contracts and fleeing – i.e. refusal to submit to forced labor.

But they weren’t brought before the court on those grounds. So what were the grounds?

With Ciriaco Santoni, whose personal information was not reported, they were among six Italians who fled their workplace in the Enns valley of upper Austria on June 3, 1944.

They traveled by rail to Tyrol and then went on foot to the upper Salzach valley in the Pinzgau quarter of Salzburg – where they tried to cross over the Alps into Italy. They were trying to get home when they were stopped by the gendarmes on June 9, 1944.

On what grounds? Because they were suspected of being fleeing forced laborers and because Italians were suspect in general. Italians had been called traitors ever since Italy abandoned its alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary during the First World War and attacked Austria-Hungary, but this theme was revived and strengthened when, on September 8, 1943, Italy changed sides during WWII and Italy was denounced as a traitor and enemy.

The Italian capitol city Rome was liberated from its German occupation forces on June 4, 1944 – just a few days before the six refugees were arrested in the Salzach valley in the hinterland of the approaching front lines (along with the combat units of the Italian Resistance on the one hand and the massacres by SS units of Italian partisans and civilians on the other).

The criminal files KLs 76/44 ignored the reality of the war across the Alps and simply claimed that »the violence in a lonely mountain district during wartime« had been provoked by an »overbearing« Italian – a formulation that implies a real threat behind the lines by six citizens of a traitorous enemy country.

Ciriaco Santoni, identified as the ringleader, was alleged to have attacked the armed gendarme when the gendarme tried to arrest him on a mountain path by the Krimml creek on June 9, 1944.

In any case, the unarmed »ringleader« was killed by two shots in the head. The uniformed shooter was then supposedly attacked by the others with fence rails: self-defense or counter-attack by the Italians, but for the authorities it was violent resistance to lawful authority and that made them »violent criminals«.

Their distress and the motivation for their flight were of no significance, nor was the deadly shooting of Ciriaco Santoni, who was buried anonymously like other »dishonorable« victims.

(thanks to information provided by his grandson Paul we now know that Ciriaco Santoni was born in Madonna di Forneli, Emilia-Romagna on January 29, 1902, was married to Andreina Caporali, and was the father of two children – Valleda and Fernando.)

The interrogation records and the prosecutor’s indictment were lost along with the shredding of the original criminal files KLs 76/44. It is clear though that the Austrian lawyer who was the chief prosecutor in Salzburg, Dr. Stephan Balthasar, drew up the charge sheet and the paragraphs laying out the reasoning for applying the death penalty.

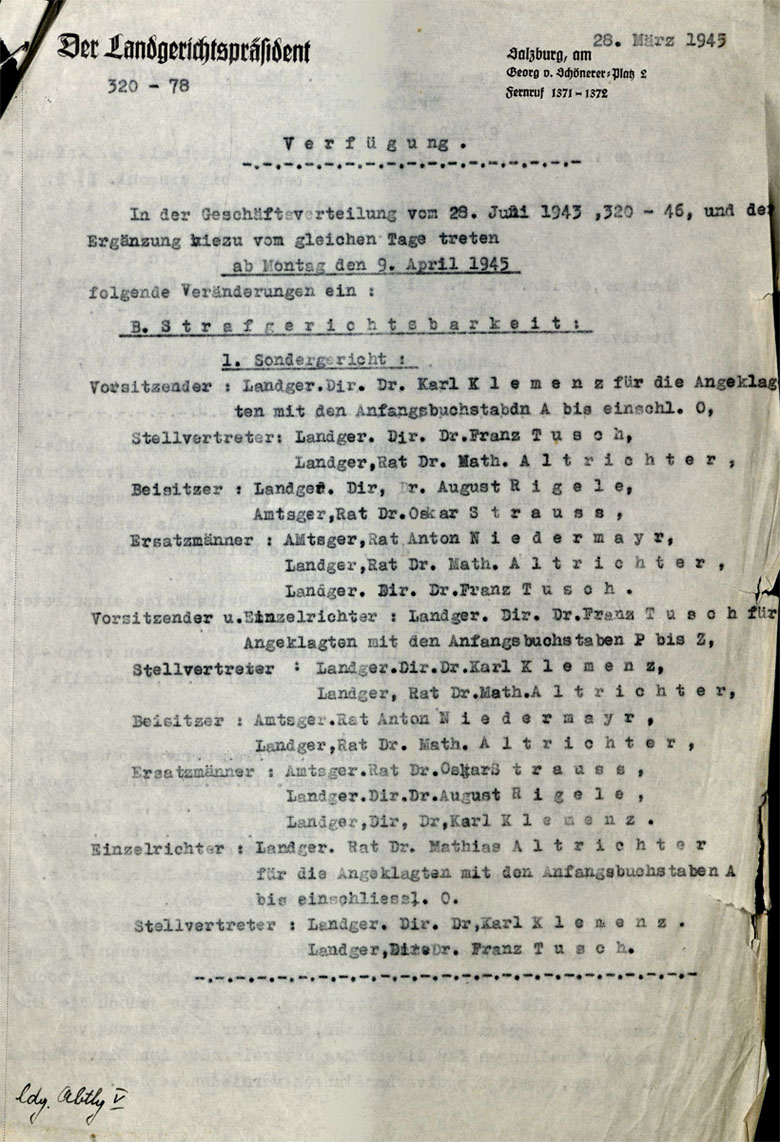

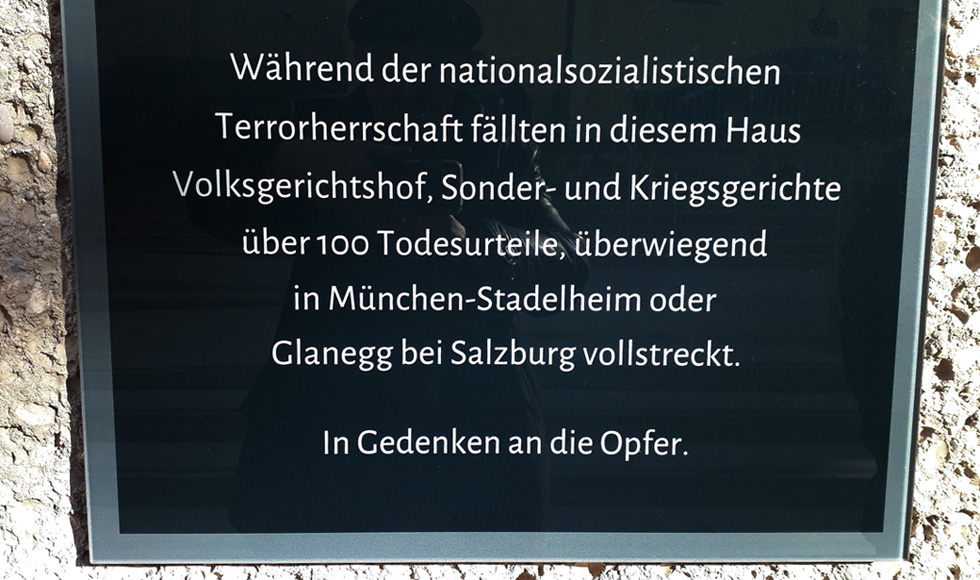

That information was included in the seven page judicial decision that was included in the Munich implementation files. There we see that the trial of the five Italians took place on August 2, 1944 in the Salzburg courthouse on the Rudolfsplatz [which, during the Nazi years, was named after the prominent Austrian German-nationalist politician and virulently Antisemitic agitator of the late 19th and early 20th century, Georg von Schönerer].

The judges of the »Special Court« were all Austrian lawyers without exception, though they had German official titles: »State court judge« Dr. Franz Tusch as presiding judge, with »State court judge« Dr. Matthias Altrichter and »State court judge« Anton Niedermayr as fellow judges – along with prosecutor Dr. Rolf Blum, and a German lawyer as defense counsel.

The »officially designated defense consul« for the Italian defendants with no criminal records and who didn’t speak any German was not named. That alone demonstrated the abuse of their right to protection against state violence and arbitrariness. Did the defense council know the sentence before the beginning of the trial?

He knew at least that appeals against »sentences handed down in the name of the German people« were not appealable.

The »Special Courts« were instruments of a politicized criminal justice system: rapid fire courts that executed the decrees of the Nazi dictatorship from first to last and were complicit in the dictatorship’s war crimes. Strangely from today’s perspective, Austrian laws were applied during the Nazi dictatorship in Austria as if they were still in force – except when in conflict with the special war ordinances of the »Council of Ministers for Imperial Defense« under Hermann Göring’s chairmanship – in this instance where the German »law against violent criminality« of December 5, 1939 set a death penalty, in contradiction to the Austrian law that was still in effect that provided for a maximum of five years imprisonment for resisting the police with armed force and reserved the death penalty for murder alone.

In order to hand down a death sentence the »special court« had to consider the fence rails used against the gendarmes as »deadly weapons«, the fatal shooting as justified, and the alleged attempted murder and helping the resistor as the equally heinous as an actual murder of a gendarme.

But even for the Nazi judges the facts here were ambiguous. As a result, and seemingly with the agreement of the chief prosecutor, on August 2, 1944 the Salzburg »Special Court« sentenced only three of the five Italian defendants to death for violent criminality – resistance to lawful authority in violation of §§ 81 and 82 of the Austrian criminal code, but added in association with § 1 Abs. 1 of the »regulations against violent criminals« because »this statutory authority requires the death penalty« (Sentence KLs 76/44).

The 22 year old Pietro PIRONI, the 20 year old Giuliano SBIGOLI and the 32 year old Remo SOTTILI were transferred to the Munich-Stadelheim prison on August 19, 1944. There, in two minute intervals at 17:01, 17:03 and 17:05 on August 29, 1944 they were guillotined by executioner Johann Reichhart.

The University of Erlangen anatomy department kept the three bodies for medical instruction without the knowledge of their families. After the end of the war the mother of Giuliano SBIGOLI attempted to discover if he had been given the Last Rites and where his grave was located as »this would be a great consolation for a mother.« She was at least able to get her son’s ID photo that had been included in his implementation file.

Goffredo BONCIANI und Vasco POGGESI, who had been found not guilty »for lack of evidence« against them, were not set free. Instead they were turned over to the Gestapo who first held them in the police jail on Salzburg’s Rudolfsplatz, and then on September 28, 1944 deported them to the Flossenbürg concentration camp where they were registered as »protective custody prisoners« numbers 27282 and 27283. On October 23, 1944 POGGESI was transferred to Mauthausen and then to the Mauthausen branch camp at Gusen – where the 22 year old was murdered on February 4, 1945.

On February 26.1945 the 23 year old BONCIANI was killed in a Flossenbürg branch camp at Lengenfeld.

The six Italians who had attempted to flee over the Krimmler Tauern Alps were dead before Italy and Austria were liberated, but this was not all. According to the prisoner records of the »SS Economic and administrative main office« at least 29 Italians, including activists of the Italian Resistance, were sent by the Salzburg Gestapo to diverse concentration camps in the year and a half between September 8, 1943 (when Italy officially left the Axis) and the final liberation of Italy from German occupation in 1945. In addition to BonciANI and POGGESI 18 of them also were killed in the camps:

• Vincenzo Bottaro, born in Milan on April 21, 1922

• Natalio Brizzi, born in Rome on December 28, 1915

• Silvestro Chinellato, born in Mogliano (Veneto) on November 19, 1910

• Roviglio Della-Schiava, born in Sedegliano (Udine) on October 5, 1914

• Anacleto De Martin, born in Tarzo (Treviso) on November 6, 1918

• Giuseppe Marcon, born in Vicenza on August 6, 1923

• Amilcare Martelli, born in Malalbergo (Bologna) on June 14, 1923

• Giuseppe Massani, born in Fucecchio (Florence) on July 29, 1902

• Domenico Musso, born in Ribera (Sicily) on August 23,1903

• Paolo Santoni, born in Force (Ascoli Piceno) on October 2, 1912

• Salvatore Savarino, born in Aragona (Sicily) on January 2, 1893

• Alfredo Veruso, born in Fiume (now Rijeka in Croatia) on December 26, 1920

• Carlo Vitale, born in Naples on January 31, 1910

• Angelo Vogrig, born in San Leonardo (Udine) on September 7, 1912

• Evaristo Zalambani, born in Fusignano (Ravenna) on May 23, 1901

• Santo Zampieri, born in Venice on June 29, 1912

• Luigi Zanga, born in Albano (Bergamo) on October 15, 1912

• Emilio Zanon, born in San Michele (Veneto) on July 24, 1896

The concentration camps where the 20 murdered Gestapo prisoners from Salzburg who have been researched so far were killed include: Natzweiler-Struthof, Dachau, Neuengamme, Flossenbürg, Lengenfeld, Mauthausen, Melk, Gusen and Ebensee.

In the end phase of the war the Salzburg »Special Court« led by Dr. Klemenz and Dr. Tusch – along with co-judges Dr.s Altrichter and Niedermayr – issued three more death sentences for Italians: Arcangelo PESENTI, a forced laborer for the German Reichsbahn railways in Salzburg who was decapitated in the Munich-Stadelheim prison on January 31, 1945 [a Stumbling Block was laid for him in front of the Salzburg main railway station on January 27, 2015];

Domenico Vallebona and Guerrino Bozzato who were forced laborers in Kaprun (c. 100 km south of Salzburg) and who were decapitated in the Munich-Stadelheim prison on March 9, 1945 and April 10, 1945 respectively and then buried in the Italian Military Cemetery in Munich.

Six death sentences carried out against Italians and a total of 26 Italians who were fatal victims of the Salzburg Gestapo – persecuted in revenge for the »Badoglio-Betrayal«, the change of sides by Italy and the liberation struggle of the Italian Resistance – which was also met with retribution from Mussolini’s »Black Brigades« and SS units who shot or hanged partisans and civilians alike. In one incident in Bassano del Grappa some 31 young hostages were killed on September 26, 1944 on the orders of SS-Obersturmführer Herbert Andorfer, who had begun his SS career in 1933 as a member of the 76th SS-Standarte in Salzburg. [Andorfer continued to live in Salzburg with his family for the rest of his life and was never prosecuted – he died in Salzburg at age 92 on October 17, 2003 and is buried in the Salzburg municipal cemetery]

It has taken a long time to research the identities and fates of the Italian victims from Salzburg as they were neither recorded in the city police registrations nor in the documentary study on resistance and persecution in Salzburg [Widerstand und Verfolgung in Salzburg 1934-1945] published in 1991.

The same is true for some Wehrmacht soldiers who had gone over to join the Italian Resistance forces: Johann SCHUCHLENZ from Salzburg was executed by the SS for wartime treason just 15 days before the German surrender in Italy.

It is said that the prosecution of war criminals began with the liberation, at least when the perpetrators could be caught. But the »First Salzburg War Criminal List« published in June 1946 – and that was the only one ever drawn up – included just 24 names, mostly Gestapo agents and not a single prosecutor or judge.

It would seem that they were considered above suspicion, or were at least too well connected to be brought to justice.1

1 In May 1945 the US occupation authorities closed all the courts in Salzburg and removed the judges from office who had held leading positions or been members of the Nazi party and its associations, including: the leader of the prosecution office, chief prosecutor Dr. Stephan Balthasar, the prosecutors Dr. Friedrich Blum, Dr. Ludwig Gandolfi, Anton Heim and Dr. Friedrich Stainer, the presiding judge of the Salzburg State Court Walter Lürzer, the judges Dr. Matthias Altrichter, Dr. Paul Kemptner, Dr. Karl Klemenz, Josef Hinterholzer, Anton Niedermayr, Dr. Julius Poth, Dr. Franz Tusch, Dr. August Rigele, Dr. Oskar Strauß and Dr. Ferdinand Voggenberger.

A few of the dismissed lawyers were interned for a while in the US prison camp Marcus W. Orr – known as the Glasenbach camp because the soldiers who guarded it were housed in the nearby Glasenbach barracks. A few were not dismissed because they had already retired before 1945: for example Dr. Hans Meyer, who had presided over the »Special Court« from 1939 to 1943, and Oskar Sacher, who led the office for prosecuting cases of miscegenation and served as co-judge on the »Special Court« until July 1943. No lawyer was ever held responsible for any of the numerous death sentences: 71 in total, 26 under the leadership of Dr. Hans Meyer and 45 under the leaderships of Dr. Karl Klemenz and Dr. Franz Tusch. Nine judges served under their leadership as co-judges and also voted for the death sentences: Dr. Matthias Altrichter, Josef Hinterholzer, Walter Lürzer, Dr. Hubert Meder (died in 1945), Anton Niedermayr, Dr. Julius Poth, Dr. August Rigele, Oskar Sacher and Dr. Oskar Strauß.

As Chief prosecutor Dr. Balthasar was one of those most responsible for the death sentences and he had been a Nazi party member since 1933 and was an SS-Sturmbannführer. That led him to be categorized as a Nazi »offender«, but he was pardoned by Austrian President Karl Renner in 1950.

Most of the judges and prosecutors were classified as »minor offenders« and were cleared by the »lesser offender amnesty« of 1948. The younger ones among them were then able to resume their careers: for example Dr. Poth, Dr. Rigele, Dr. Tusch and Dr. Voggenberger returned as attorneys, Dr. Gandolfi became an administrative judge for the city and then a judge for courts in Salzburg and Linz. Dr. Karl Klemenz, who had participated in at least 29 death sentences but who was never registered as a Nazi, had already been restored to a judgeship in 1947, although it was just for a district court in Leoben.

He made a political career in the »Association of Independents« which represented the interests of former Nazis and in 1949 he became a member of the Federal Council – the second chamber of the Austrian parliament [the equivalent of the U.S. Senate].

Dr. Matthias Altrichter, who had participated in at least 32 death sentences, was also classified as a »minor offender«. This was despite his Nazi party membership (May 1, 1938: Number. 6,347.572, and thus holder of one of the membership numbers reserved for »Old Party Comrades« [from 6,100.001 to 6,600.000]). Worse still, he was classified as a »minor offender« despite his SA Stormtrooper and SS memberships (he was a Senior Squad Leader [Oberscharführer] in the SA and a patron member of the SS with membership number 1,403.697 [patron members were not active in the SS, but they made monthly contributions to it]) and despite his leadership functions in the Nazi Regional Legal Office and the Nazi Legal Confederation.

Hardly had he been amnestied in 1948 when he again served as a judge, becoming a presiding judge and then President for the Salzburg State Court from 1958 to 1968 – for which service he was honored with the Large Silver Medal of Honor of the Austrian Republic and the City of Salzburg ring of honor [State Capitol City Salzburg Gazette, May 15, 1969].

There was a long silence about one victim of Salzburg’s Nazi justice system: the high court justice Johann LANGER. LANGER had been »furloughed« when the Nazis took over in March 1938 and had put an end to his life in the Dachau Concentration Camp.

On August 28, 2008 a Stumbling Block was laid in front of his last Salzburg residence with the participation of Dr. Philipp Bauer, the vice-president of the Salzburg State Court.

On that occasion Dr. Bauer called for the further examination of the history of the Salzburg justice system under the Nazi regime and the personnel continuities after 1945. That has begun.

Sources

- Salzburg City and State archives

- Bavarian Main State Archive in Munich (Implementation files JVA 543, 612, 619)

- Nazi Documentation Center of Munich

- SS-Economic and Administrative Main Office (Prisoner Cards Gestapo Salzburg)

- Enciclopedia dell’antifascismo e della Resistenza

- Claudio Riva: Pietro Pironi – ribelle per amore (Cesena 2007)

- Sonia Residori: Il massacro del Grappa (Verona 2007)

Translation: Stan Nadel

Stumbling Stone

Laid 28.09.2017 at Salzburg, Rudolfsplatz 2

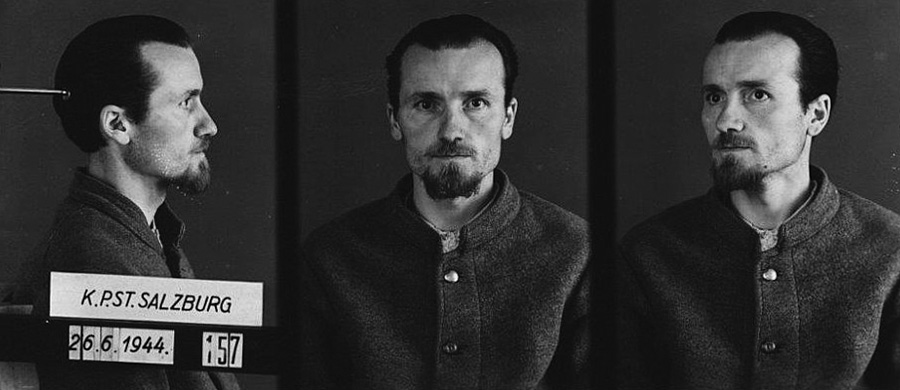

Remo Sottili

Remo SottiliSource: Munich city Archives

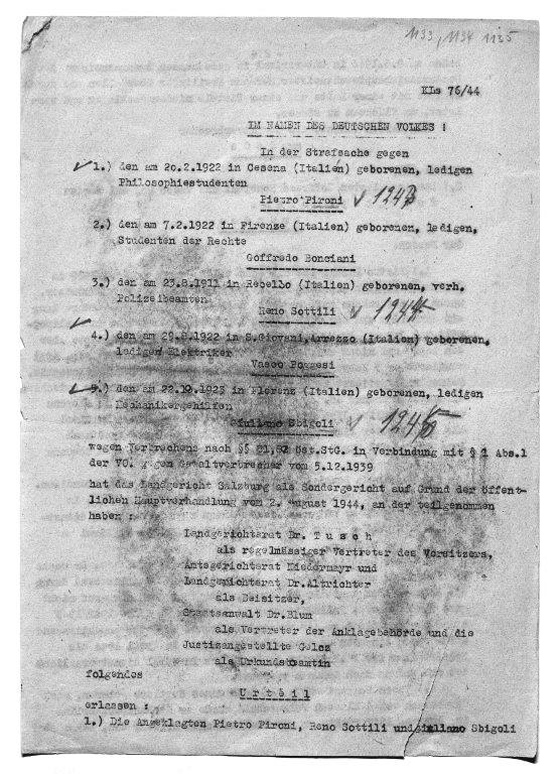

Death Sentence of the Salzburg Special Court from August 2, 1944

Death Sentence of the Salzburg Special Court from August 2, 1944Source: Munich city Archives

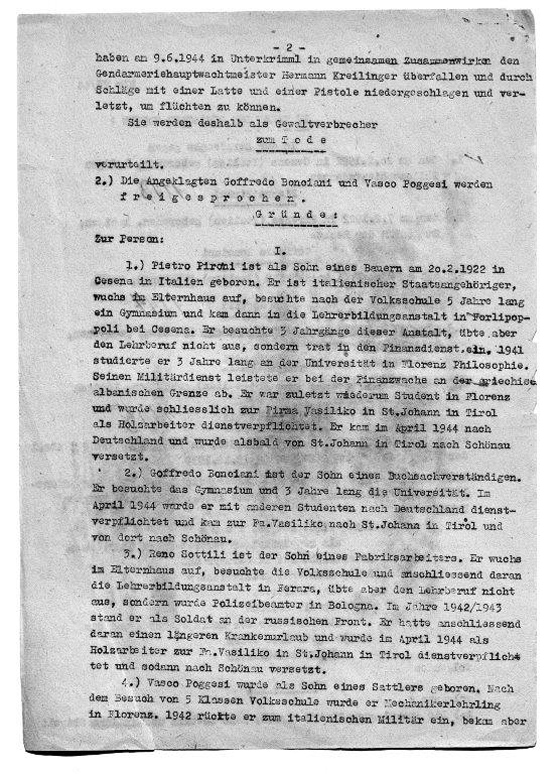

Death Sentence of the Salzburg Special Court from August 2, 1944

Death Sentence of the Salzburg Special Court from August 2, 1944Source: Munich city Archives

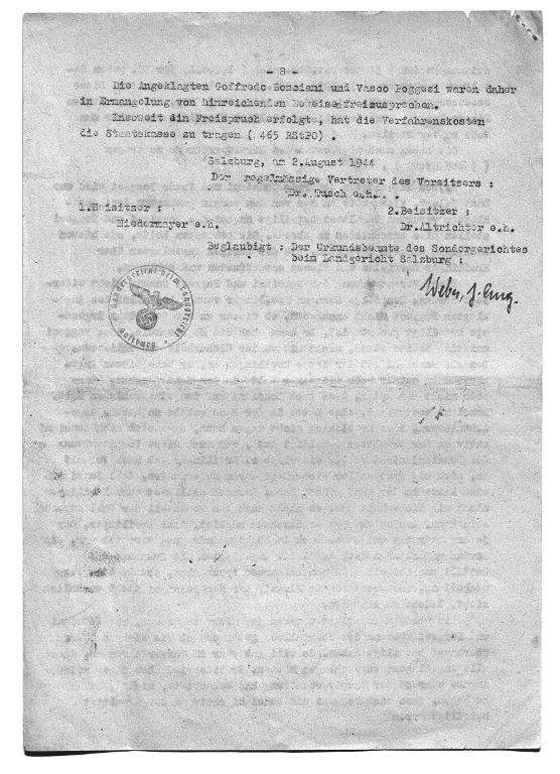

Death Sentence of the Salzburg Special Court from August 2, 1944

Death Sentence of the Salzburg Special Court from August 2, 1944Source: Munich city Archives

The judges of the Salzburg Special Court

The judges of the Salzburg Special CourtSource: Salzburg state archives

The symbol of the Nazis' civil and military courts: A sword and scales of justice combined with the Nazi Party eagle and swastika

The symbol of the Nazis' civil and military courts: A sword and scales of justice combined with the Nazi Party eagle and swastika

Photo: Gert Kerschbaumer

Photo: Gert Kerschbaumer