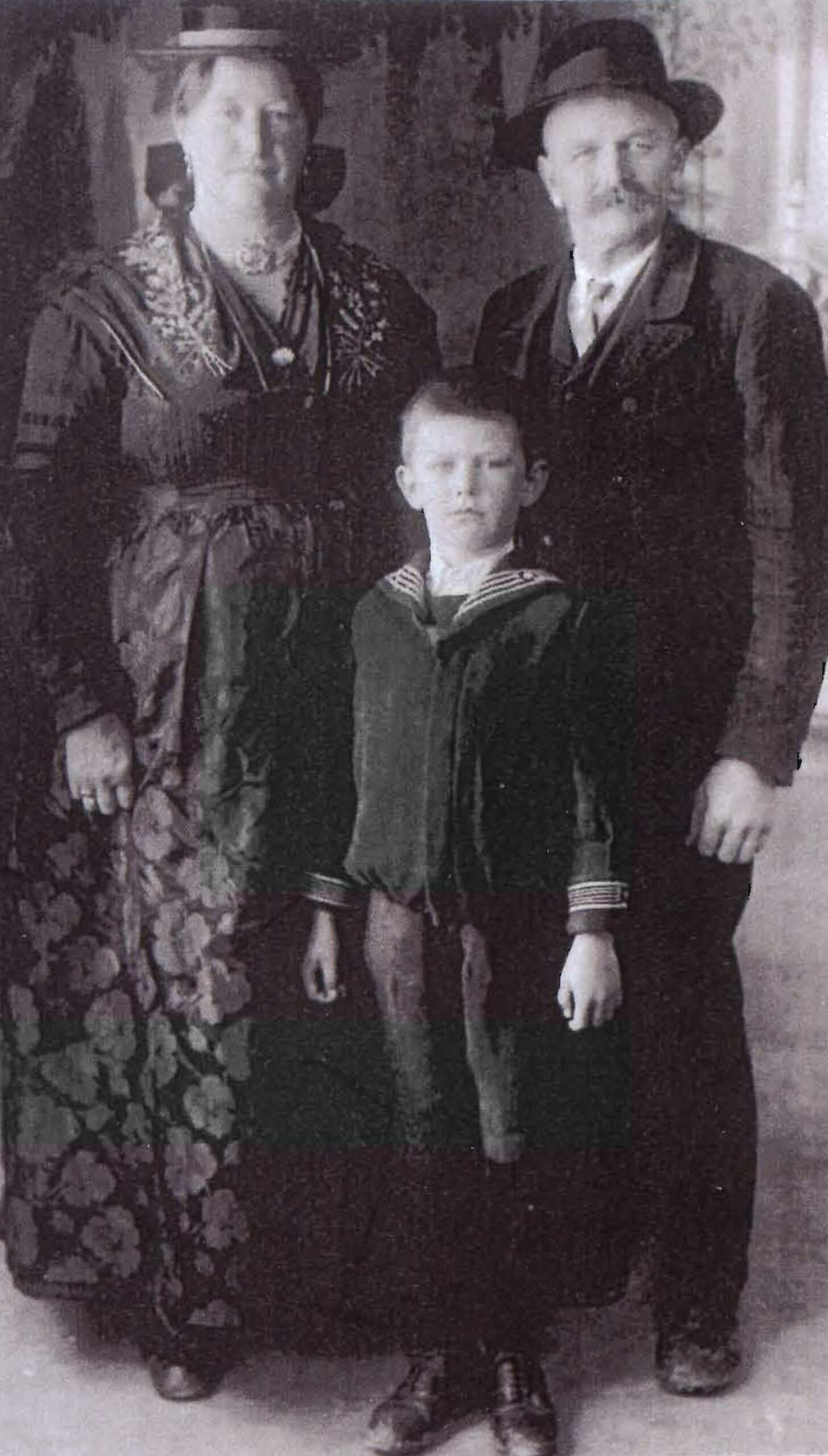

Georg »Schorsch« KÖSSNER was born 80 kilometers south of Salzburg in Goldegg-Weng on July 30, 1919. He was baptized in the Roman Catholic Church and was the only child of Therese Kössner, née Holzmann, and Georg Kössner, a farmer and innkeeper a few kilometers away at Mitterstein 4.

In November 1941 »Schorsch«, the heir to the farm, married Therese Eder (who had been born in nearby Eschenau in 1921). The couple had four children: Georg, Johann, Maria and Christian – the youngest of the four was born on March 7, 1945, the day before his 25-year-old father, who had refused military service in the German Wehrmacht, was executed.

During his eight-month imprisonment in Salzburg, his mother died in Goldegg at the age of 64. His 23-year-old wife, and his 67-year-old innkeeper father who had offered board and lodging to several deserters, fell into the clutches of the Gestapo on July 2, 1944.

Therese was released from police and concentration camp imprisonment on October 24, 1944 because she was pregnant, just a few days before the criminal proceedings began against her husband who was imprisoned in Salzburg.

But how could his family have helped him?

Georg’s father, who had been a Christian-Social mayor in the 1920s and an official of the Fatherland Front under the Austrian dictatorship, was considered an opponent of the Nazi regime.

In the 13-page »interim report« by the Salzburg Gestapo of July 20, 1944, political judgments were made on opponents of the regime:

The father Georg Kössner strongly encouraged the deserters in their traitorous attitude.

In the Gestapo report the deserters were accused of having committed »treason« because they had committed acts of resistance against a terrorist regime that was waging a war of robbery and extermination.

That was why the Gestapo, under the command of Georg König and Josef Erdmann, used extreme violence to track them down in Goldegg on July 2, 1944: including murders, brutal interrogations, abuse, convictions and deportations.

The Gestapo had the 67-year-old farmer Georg Kössner deported to Dachau in August 1944. He experienced the liberation of the concentration camp in April 1945 and was able to return home to Goldegg.

Georg KÖSSNER junior had hoped to escape the death penalty imposed on October 30, 1944 through a pardon because his Goldegger companion Richard Pfeiffenberger had gotten one.

But Pfeiffenberger was hardly let off the hook, he was assigned to the Eastern Front after his pardon and became a Soviet prisoner of war. He had been wounded and died in captivity in Retschyza am Dnepr on September 21, 1946 at age 22.

The court-martial verdict on Richard Pfeiffenberger from September 13, 1944 provides information about the Goldegger deserters from the Nazi point of view: Georg KÖSSNER was given a bad report. It began with denunciation and slander and ended in judicial murder.

The search for the death sentence against Georg KÖSSNER has been unsuccessful so far. The missing papers were apparently among the court-martial files that were burned towards the end of the war to protect the bloody handed judges.

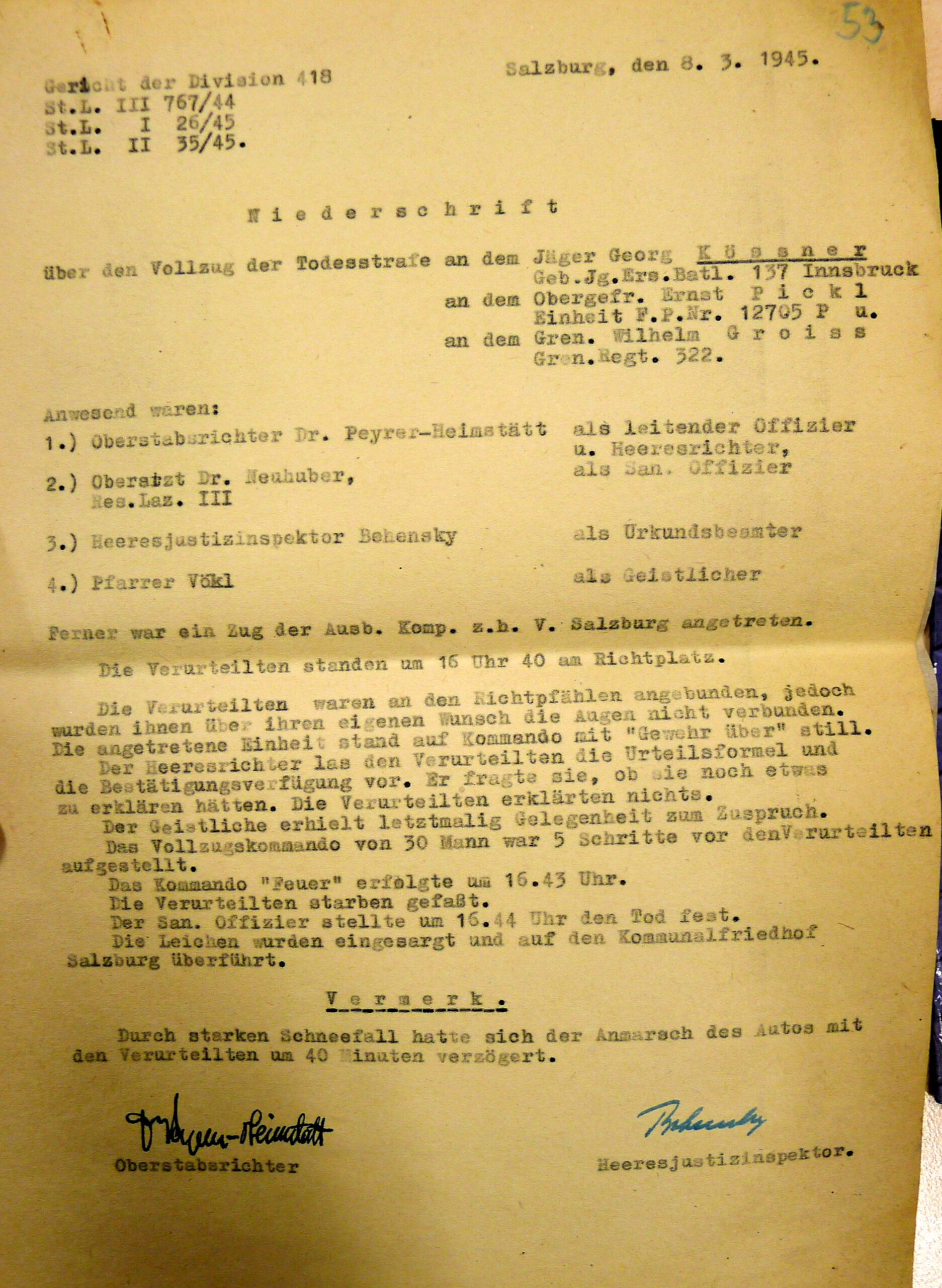

One document did survive the destruction of so many files: the minutes of »Chief of Staff Judge« Dr. Erich Peyrer-Heimstätt1 of March 8, 1945 on the execution of three young deserters from the German Wehrmacht in the final phase of the war of extermination.

That document is why we know that the Court-Martial of Division 418’s death sentences against 20-year-old Ernst PICKL, 25-year-old Georg KÖSSNER and den 26-year-old Wilhelm GROISS were carried out by a 30 man execution squad on the military firing range neat Salzburg in Glanegg at 4:30 in the afternoon of March 8, 1945.

It is also documented that three young people were killed on that same day, at the same time and in the same place who were buried in the municipal cemetery in Salzburg – but anonomously under orders from the Court-martial designed to prevent any honoring of the dead, not even obituaries – damned to be forgotten, damnatio memoriae. Their names were supposed to be erased from all collective memory.

But there was a witness: Karl Völk, the pastor of the Wehrmacht base in Salzburg who had to accompany the deserters from their cell to their execution. The priest was deeply touched by the severe suffering of the KOESSNER family:

I visited Kössner once a week and more often. His wife was in a concentration camp, as was his father. The woman came home in November 1944 because she was expecting a child.

After the death sentence, Kössner waited 4 months for a pardon, which was then rejected. He was made to wait until the child was born. This then brought about a tragedy.

The child was born the day before the execution.

The next day the postman brought a letter to the woman who had recently given birth and she believed that a pardon would be communicated to her. Full of joy, the woman opened the mail, which reported the death sentence that had been carried out. You can imagine the terror; and on top of that with a woman who had just recently given birth, it was the 4th child.

(Witness report by Priest Karl Völk on February 25, 1964)

Thanks to his report, it is also known that the corpse of Georg KÖSSNER was exhumed in Salzburg in August 1945 and buried in the presence of his family in his home town of Goldegg.

On the other hand, the applications made by his father and his widow in liberated Salzburg for »official certificates« for victims’ compensation with entitlement to pensions were rejected. They were not regarded as »victims of the struggle for a free, democratic Austria«2.

Nor were they acknowledged by name in the public spaces of their hometown of Goldegg – damned to be forgotten (damnatio memoriae) in the long shadow of Nazi rule in Austria.

However, there is no lack of civil courage. Thanks to the initiative of Brigitte Höfert (daughter of Karl Rupitsch, who was murdered in Mauthausen) and Michael Mooslechner, a memorial stone designed by the sculptor Anton Thuswaldner with the names of 14 women and men3 who resisted was erected on private property in Goldegg in August 2014.

On the other hand, it turns out that the names carved in stone are undesired even on the outskirts of Goldegg. The memorial stone was smeared with paint at the beginning of September 2018 to render it illegible.

The perpetrators were never caught.

1 Dr. Erich Peyrer-Heimstätt (b. 1899, d. 1977 in Salzburg), civil profession notary, served during the war years 1944/45 as »chief staff judge« of the Court Martial for Division 418. In liberated Austria he resumed his previous civilian career and was later a member of the Board of Trustees of the International Mozarteum Foundation and President of the Friends of the Salzburg Festival.

2 Federal law of July 4, 1947 on the welfare of the victims of the struggle for a free, democratic Austria and the victims of political persecution (victims’ compensation law)

3 Goldegg memorial stone with the names of the terror victims: Alois and Theresia Buder, Theresia Bürgler, August Egger, Maria and Rupert Hagenhofer, Alois and Simon Hochleitner, Georg Kössner, Alma Netthoevel, Peter Ottino, Richard Pfeiffenberger, Karl Rupitsch and Kaspar Wind – THE VICTIMS OF THE »STORM« IN GOLDEGG-WENG ON JULY 2, 1944 AND ALL THE SURVIVORS OF THE CONCENTRATION CAMPS

Sources

- Salzburg State archives: Victims’ compensation and court files, 13-page interim report by the Salzburg Gestapo (Dr. T. Grafenberger) of July 20, 1944

- Archive of the Salzburg Archdiocese: Register books and military registers

- Austrian State archives: Death sentence of the Court-Martial of Division 418 (Dr. Wilhelm Krepper) against Richard Pfeiffenberger of September 13, 1944, minutes of the court-martial of Division 418 (Dr. Erich Peyrer-Heimstätt) of March 8, 1945

- Documentation Archive of the Austrian Resistance: Witness statement of Karl Völk, Dean of St. Johann im Pongau, from February 25, 1964

- Michael Mooslechner and Robert Stadler: St. Johann im Pongau 1938-1945. Das nationalsozialistische »Markt Pongau«. Der »2. Juli 1944« in Goldegg – Widerstand und Verfolgung, Eigenverlag 1986

- Die Goldegger Wehrmachtsdeserteure. Gedenkstein 2014, published by the Verein der Freunde des Deserteursdenkmals in Goldegg, May 2019

- Salzburg city archives: Salzburg city archives: report from the cemetery administration dated January 21, 2022

Translation: Stan Nadel

Stumbling Stone

Laid 27.09.2022 at Salzburg, Kajetanerplatz 2

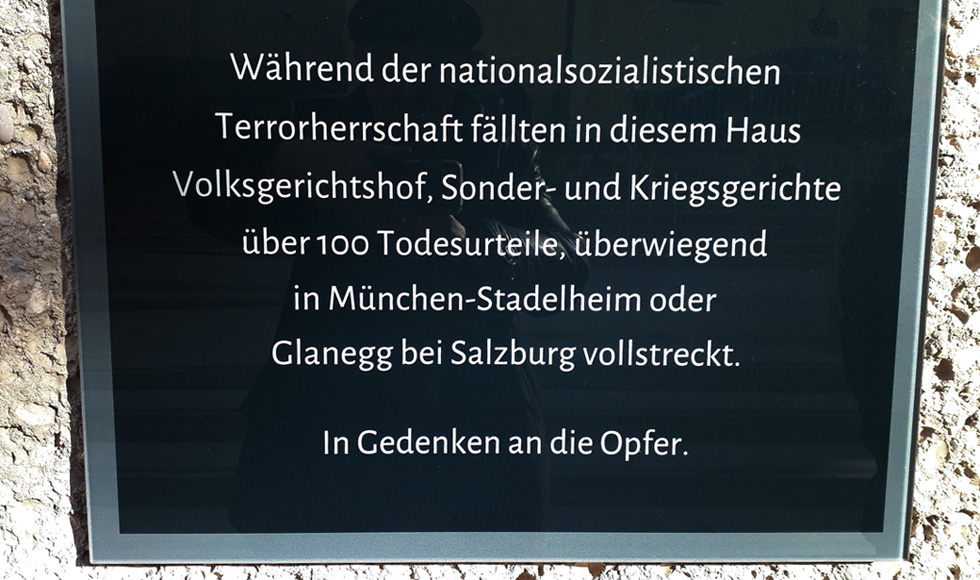

Memorial plaque at the Salzburg State Courthouse

Memorial plaque at the Salzburg State CourthousePhoto: Gert Kerschbaumer

The young »Schorsch« with his parents Therese and Georg Kössner

The young »Schorsch« with his parents Therese and Georg KössnerFrom: Die Goldegger Wehrmachtsdeserteure

Division 418 Court-Martial report from March 8, 1945: »Command fire«

Division 418 Court-Martial report from March 8, 1945: »Command fire«

Photo: Gert Kerschbaumer

Photo: Gert Kerschbaumer

Memorial to the victims of the Salzburg courts martial in Glanegg (erected on 30 September 2011 on the initiative of Governor Gabi Burgstaller)

Memorial to the victims of the Salzburg courts martial in Glanegg (erected on 30 September 2011 on the initiative of Governor Gabi Burgstaller)Photo: Gert Kerschbaumer